Cogent Raises $42M Series A - Read more here

Feb 9, 2026

Agents That Only Watch: Building the Supply Side of Context

The most important agents in your stack will never close a ticket.

Anirudh Ravula, Head of AI

Introduction

Every enterprise AI agent today has credentials to dozens of internal systems — ticketing platforms, knowledge bases, internal wikis, monitoring tools, cloud consoles — and can extract data from any of them on demand. What they don't do — is spend time understanding the environment before a task arrives. The raw material for that understanding is already there, scattered across the sources those agents connect to: which fields actually matter here, how services really depend on each other versus what the architecture diagram claims, what "critical" means given this specific infrastructure and these specific customers. An agent could derive most of it through sustained cross-source reasoning — the same investigative work a senior employee does in her first months. But today, most deployed agents are task agents: they wake on prompt, race to answer, and shut down.

Context engineering has gotten a lot of attention over the past year, and for good reason. In June 2025, Shopify CEO Tobi Lutke endorsed the term; a week later, Andrej Karpathy gave it a definition that stuck: "the delicate art and science of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step."

Anthropic formalized the discipline by September. Manus extended it with production-tested patterns. LangChain offered a framework of Write, Select, Compress, and Isolate. Then the frame expanded: Foundation Capital introduced context graphs, Animesh Koratana of PlayerZero proposed that agent work trails become the graph, and by January Glean was calling context "the next data platform." Context engineering went from a window-level concern to a broader infrastructure conversation.

What we've found building agents for enterprise security is pretty simple: all of the above works great for the read side — retrieval, RAG, GraphRAG, all the ways to get existing information into the window at the right time. Where it breaks down is building the understanding in the first place. In environments with hundreds of vulnerability scanners, asset inventories, cloud configs, all changing daily — the underlying understanding often isn't there to optimize. And what does exist is scattered across systems in ways that are hard to index. Runtime optimization assumes there's something good to retrieve. Often there isn't.

That's what led us to think about agents whose entire job is to watch.

Agents That Only Watch

The Supply Gap

The industry has gotten good at the demand side of context — curating what goes into the window at inference time. Runtime optimization, token budgets, retrieval strategies. And Foundation Capital's "context as exhaust" model adds a compelling supply mechanism: let agents do real work, capture their trajectories, and the graph builds itself over time.

We think both are necessary and neither is sufficient. Not for enterprises.

A typical enterprise has hundreds of apps. Less than a third of them talk to each other. The environment changes constantly:

Containers spin up

Security groups get modified

Teams reorg

Services get quietly deprecated

A vulnerability that was irrelevant last week becomes critical because someone changed a firewall rule. What was true about your environment yesterday is already partially wrong today.

Exhaust works once agents are productive. Runtime optimization works when good context already exists somewhere. The question we keep coming back to: in a fragmented enterprise environment that changes daily, who is deliberately building that understanding in the first place? And who keeps it current?

Supply-Side Agents

That's the case for dedicated background agents. Not task agents repurposed. Not a side effect of other work. Agents whose sole purpose is to observe the environment, map what matters, and maintain that understanding as the ground shifts underneath. We call them supply-side agents — tens to hundreds of dedicated agents running continuously across your data sources. They never close a ticket. They never answer a user's question directly. We think they might be the most important part of the stack — because every other agent downstream starts with understanding instead of starting from scratch.

The difference isn't a smarter model. A task agent splits its attention between understanding the environment and completing the task, under time pressure, in a single session. A background agent has no ticket and no user waiting. It can spend a significant amount of time cross-referencing what Wiz reports about a container against what CrowdStrike sees on the host against what the CMDB says about the service owner — a correlation that requires touching all three systems with no deadline. And when it gets something wrong, a human reviewer catches it before it ever reaches a task agent.

Agents Correlate, Humans Judge

There are plenty of cases where agents can build reasonable understanding on their own — correlating data across sources, tracking what changed, mapping how services connect. The information already exists across the enterprise; it's just scattered. Given enough time and access, agents can do the homework that a human analyst would eventually do — they understand how enterprise systems relate, what fields map across tools, and how to reason about the connections. The raw material is already in the data; it just takes sustained investigation to derive it. For the rest — business judgment, organizational context, decisions that require human expertise — the architecture supports gathering context directly from humans too. Users can review findings, override mappings, and feed decision frameworks back into the context layer. Traditional tools solve pieces of this: CMDBs handle inventory, SOAR playbooks automate enrichment, platforms like Axonius normalize identity across tools. But they correlate what they're configured to correlate. They can't reason across sources to surface connections nobody anticipated, and in a fragmented enterprise, those unanticipated connections are where the real understanding lives. The agents do the cross-source reasoning. Humans provide the judgment. Both feed the same stores.

Every Agent Starts at Day One

When a senior security engineer joins a company, they don't do useful work on day one. They can't. They spend weeks, sometimes months, just learning the environment. Not the documentation. The actual environment:

Which systems matter and which ones are legacy noise

How the network is really segmented versus how the wiki says

What "critical" means here, at this company, with these assets and these customers — not what a CVSS score says generically

After months, they've built something no document gave them: a working understanding of how this place actually runs. That understanding is what makes them effective.

And that understanding isn't static. The environment changes every week: new services get deployed, teams reorganize, policies shift, infrastructure drifts. The good engineer keeps learning because the thing they learned about keeps changing. The onboarding never actually ends.

Now consider: every time you invoke an AI agent, it starts at day one. It has access to every scanner, every API, every data source in your stack. It can pull two hundred Tenable fields in seconds. It cannot tell you which five of those fields actually matter in your environment — because that understanding takes sustained observation across multiple systems, and most agent deployments aren't structured for it.

The result is agents that can connect to everything but lack proper understanding.

The gap isn't extraction — modern RAG pipelines extract fine. The gap is interpretation. Indexing your Wiz findings doesn't tell you which ones matter in the context of your CrowdStrike alerts and your actual network topology. That requires reasoning across sources, not just indexing each one.

What if the onboarding wasn't optional?

The Architecture

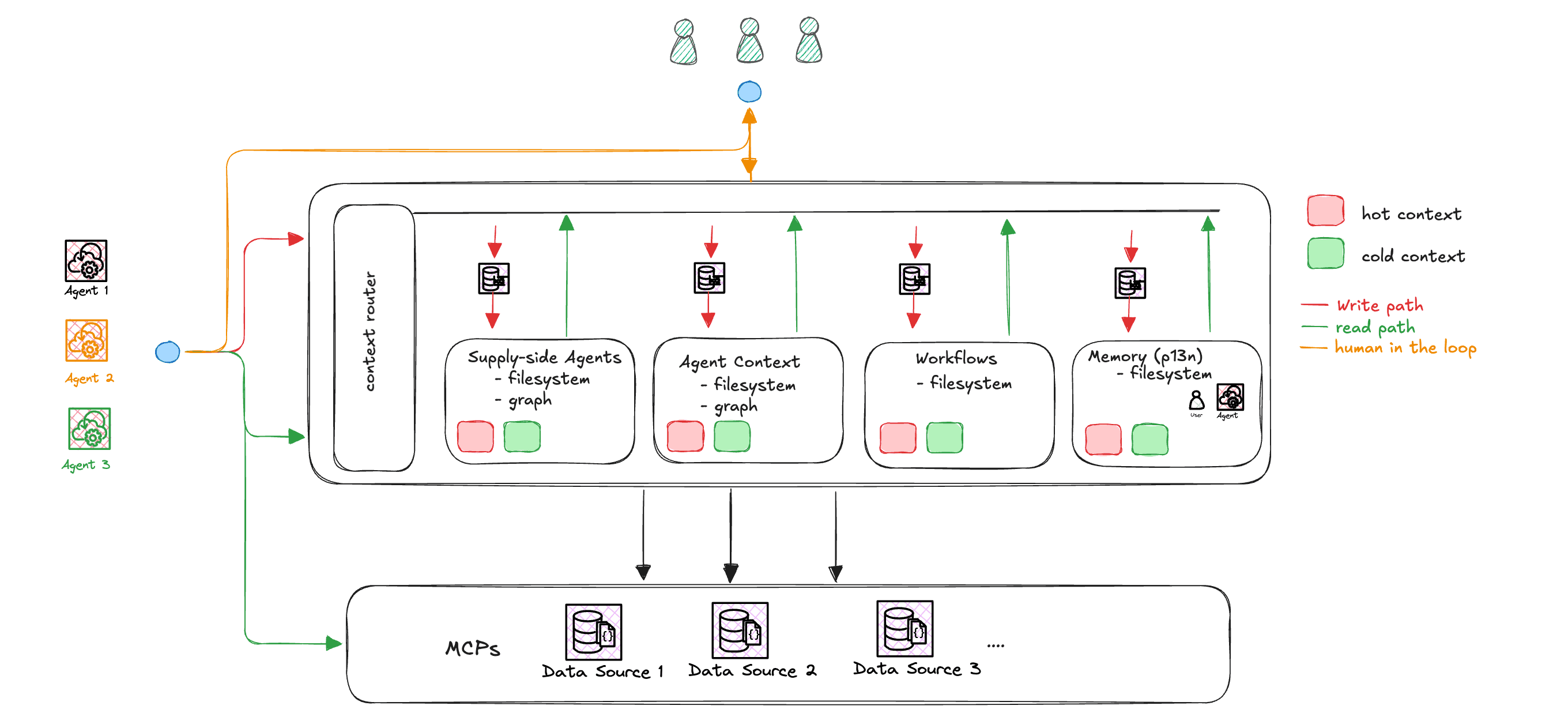

Here's roughly what the system looks like.

Environment context. What the supply-side agents have learned offline (and continues to update continuously): asset inventory, network topology, which services talk to which, what changed recently.

Agent context. Pre-computed briefs specific to this agent's role. A vulnerability triage agent gets different context than an incident responder, even when they're looking at the same asset.

Workflow context. How this organization actually does things — remediation playbooks, escalation paths, exception-handling patterns. The stuff that lives in runbooks and people's heads.

Memory. Past decisions, user preferences, patterns from previous interactions. The institutional memory that keeps agents from re-asking questions you already answered.

How Context Gets Stored

Each source maintains multiple tiers of depth:

Hot context. Distilled summaries ready to inject into a prompt. Cache-hit speed.

Cold context. The structured detail behind the summaries (roughly 100x more information), indexed and searchable in the filesystem.

Deep storage. Full enriched outputs from the agents' analysis.

Raw traces. The actual reasoning trails -- what the supply-side agents observed, queried, and concluded. The audit log of how understanding was built.

Every store is backed by filesystem. Environment context and agent context also maintain a graph for relationship queries, built autonomously by these agents as they map how things connect.

Nothing goes straight to the stores: updates hit a queue first, where a validation layer (a smaller set of agents) checks proposed changes before they're committed. It cross-references proposed updates against existing context for consistency, verifies that new findings align with what other agents have observed about the same assets, and flags anomalies for human review. Most updates pass automatically; conflicting or high-impact changes get queued. Humans can review and override at any point.

How Context Gets Served

A context router assembles the right package from all four sources for each task, fitted to token budgets. Most requests hit hot context. Some pull from cold. Deep storage and raw traces are there for when an agent, or a human, needs to understand not just what's true, but how the system arrived at it.

At runtime, task agents combine this pre-built understanding with live queries to data sources. The context tells the agent where to look and what matters; the live data gives it the current state.

Background Agents as the New ETL

The pattern resembles ETL — extract from your data sources, transform through AI that actually interprets what it finds, load into context stores that serve every downstream agent. But the output is fundamentally different. Not rows. Understanding — like knowing which six servers sit between your customer data and the internet, or that the CVE everyone's panicking about was already patched on staging two weeks ago. That understanding was always latent in the data — spread across your cloud provider, your CI pipeline, and your patch management system.

Beyond Exhaust

Foundation Capital introduced an elegant model for this: context graphs as exhaust. Agents solve real problems, their trajectories accumulate, and structure emerges from use. No upfront schema design. The economics are clean: nobody pays separately to build the graph because it's a byproduct of work the agent is already doing.

We agree with all of that. Foundation Capital’s work on how to build context graphs — agents as walkers discovering ontology through use — pushes the model further. And yet we've found that even this describes the steady state better than it describes how you get there in a fragmented enterprise.

The flywheel assumes agents already understand enough to produce useful trajectories. In an enterprise with 200 siloed applications — where "asset" means something different in Wiz than it does in ServiceNow, where the network topology lives in six engineers' heads and zero documentation — the first trajectories carry more noise than signal — typical task agents are not designed for that kind of sustained cross-source investigation — and the graph that accumulates from noisy walks inherits that noise. Dedicated background agents sidestep this — they have no task to complete, so they can spend a significant amount of time correlating across sources, building the baseline understanding that makes task agents' subsequent trajectories actually useful.

There's a less obvious gap too. Enterprise environments change constantly. But agent trajectories only cover the parts of the environment where tasks happen. A container that quietly hit end-of-life, a security group someone modified at 3am, a service that came online last Tuesday — if no task agent touched those areas, the change is invisible to the graph. What happens between the tasks is exactly what exhaust can't capture.

What we've found is that both models work better together. The supply-side agents build the foundation. Task agents start with that understanding, do better work, and contribute richer exhaust back into the context layer. Both streams feed the same stores. Not instead of exhaust. In addition to it.

What Changes — and Where to Start

Running background agents isn't free — mostly inference, some infrastructure. The economics improve with reuse: the same pre-computed context serves every downstream agent interaction, and background agents don't always need your most expensive model. Whether it's worth it depends on how much your task agents currently waste rediscovering the environment every session, and how much human effort goes into the correlation work that background agents handle continuously. With the cost of intelligence dropping dramatically, the economics only get better from here.

But the real payoff isn't the token bill. It's what happens at the point of action. An agent that already understands the environment spends fewer turns exploring, makes fewer errors from missing context, and arrives at a useful answer on the first attempt more often. The difference between an agent that starts cold and one that starts with context is obvious within the first ten seconds of watching it work.

Here's an experiment: pick the domain where your agents struggle most and build three background agents for just that domain. Have them map the sources, normalize the terminology, track what changes. You'll likely find that most of the technical understanding your team treats as tribal knowledge is actually recoverable from the data — it just required sustained correlation that nobody had time to do. Then watch what happens when your task agents start with that understanding already in place.

Context engineering taught us how agents should read. Now build the agents that watch.

The most important agents in your stack will never close a ticket.